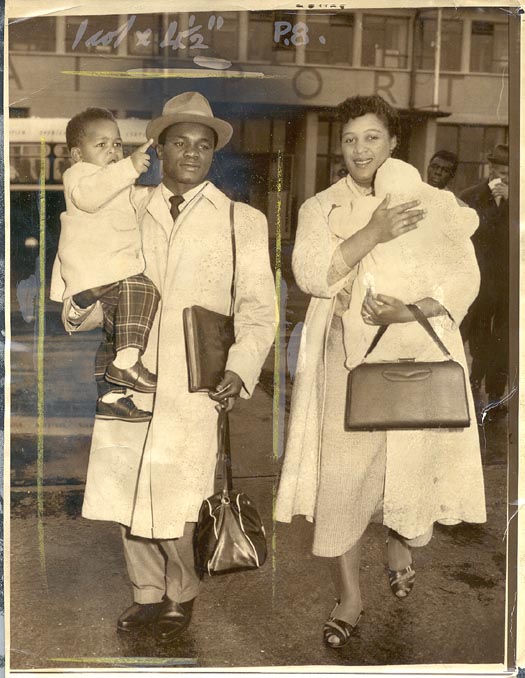

HOGAN BASSEY AND FAMILY, 1958

Featherweight boxing champion Hogan "Kid" Bassey with his wife

and two children travelling to the United States (1958 press photo). Bassey was the second

African to become a world boxing champion.

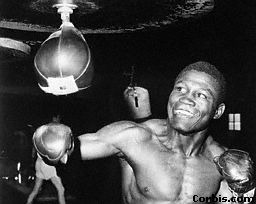

Dick Tiger punching speedbag

Dick Tiger punching speedbag

December 7, 1961

Dick Tiger flexes

arm

Dick Tiger poses with flexed arm and gloves

1962

Dick Tiger

Dick Tiger high angle with glove in camera

New York

City

March 30, 1962

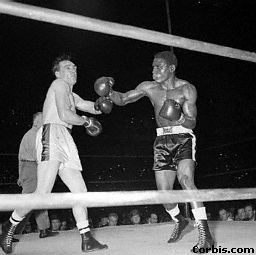

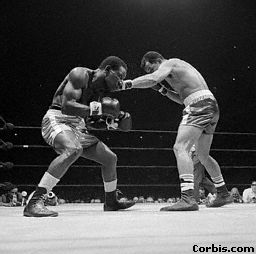

Gene Fullmer

Grimaces Dick Tiger Punches

Gene Fullmer Grimaces Dick Tiger Punches

San Fransciso, California

October 23, 1962

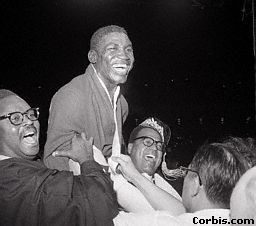

Dick Tiger Hoisted on Shoulders

Dick Tiger hoisted on shoulders after defeating

Gene Fullmer

San Fransciso, California

October 23, 1962

Dick Tiger Lifted as Victor

Dick Tiger lifted on shoulders for defeating

Gene Fullmer

San Fransciso, California

October 23, 1962

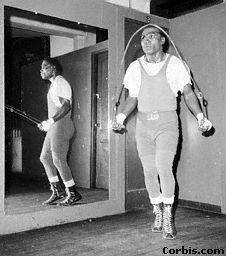

Dick Tiger in sweats skips rope, New York City, November 12, 1963

Dick Tiger in sweats skips rope

New York City

November 12, 1963

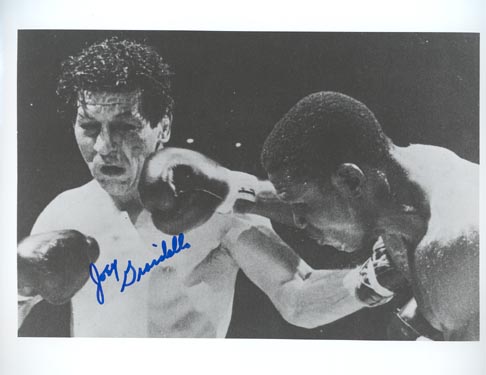

Dick Tiger fights Joey Giardello

Joey Giardello in a middleweight championship fight with Dick Tiger.

Giardello and Tiger fought 4 times from 1959 to 1965, all decision affairs,

with Giardello winning the second and third fights and Tiger the first and fourth.

Jose Torres punches Dick Tiger

Jose Torres (right) punches Dick Tiger

New York City

May 16, 1967

Dick Tiger and Bob Foster spar

Dick Tiger and Bob Foster spar

New York City

May 24, 1968

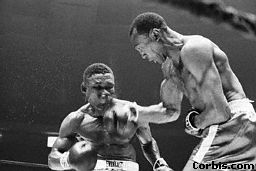

Bob Foster punching Dick Tiger

Bob Foster punching Dick Tiger

New York City

May 27, 1968

Dick Tiger knocked down by Bob Foster

Dick Tiger knocked down by Bob Foster.

New York City

May 27, 1968

PERSPECTIVE: DICK TIGER WAS A CHAMPION IN BOTH THE

RING AND HIS AFRICAN HOMELAND

(Sports Illustrated)

At some stage of their lives, most American males idolize a sports

figure. Boxing champions lend themselves particularly well to this

form of worship. Fighters like James Corbett, Jack Dempsey, Benny

Leonard, Sugar Ray Robinson, Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano and Muhammad

Ali not only were heroes of their times but also put their unique,

mythic stamps on very different generations of male American

consciousness.

I, too, got caught up in the aura and sweep of the great champions

of my lifetime. But the one fighter I identified with -- my fighter,

in other words -- was not in the same league with Leonard or Robinson

or Louis or Ali. A knowledgeable boxing critic might rank him a cut

above ''hell of a fighter.'' However, if you judged the entire man,

boxer and human being, few could match Richard Ihetu, the African who

fought under the nom de guerre Dick Tiger.

As with many professional boxers, the last part of Dick Tiger's

life was tragic. The difference in Tiger's case is that it wasn't

boxing that took the heart out of him; it was the dream that he tried

to support with the purses he earned after he had reclaimed the

middleweight title and then won the light heavyweight championship.

Years from now, when a bunch of guys in a bar are grumbling about

a mismatch on TV and start talking about good, maybe great, light

heavyweights, Dick Tiger will not be the name they settle on; it

could be Archie Moore, Bob Foster or Philadelphia Jack O'Brien. But

if they know their boxing, Tiger's name will at least be mentioned.

Helped by a notation scrawled in a spiral notebook, I recall the

day and hour I met Dick Tiger: ''Noon -- March 10.'' The year wasn't

recorded, but it was 1965. Tiger was meeting the press that day in

his dressing room at Madison Square Garden. It was two days before he

would fight Rocky Rivero, a tough middleweight from Argentina known

for his knockout punch. It didn't figure to be an easy evening for

Tiger. He was 35, and 15 months earlier he had lost his middleweight

championship in Atlantic City to Joey Giardello on what was conceded

to have been, by everyone but Giardello people, a warped hometown

decision.

Only four or five reporters had shown up, and we waited outside

the door to a 50th Street dressing room while the tap and slide of a

jump rope sounded from inside. Chickie Ferrara, Tiger's able trainer,

opened the door, and we filed in. I had seen Tiger a couple of times

on TV; I remembered one appearance in particular, a vicious 15-round

draw with Gene Fullmer. I would never have recognized Tiger in the

flesh. He was the darkest man I had ever seen. But that doesn't

entirely describe it: There was a dusky, deep plum color to his skin,

and even where he glistened with perspiration there were gray patches

that looked dry, very much like the skin of the fruit. I stared at

the knotty, heavily muscled body. I was almost oblivious to the

questions being asked and to his answers, but not quite. Our eyes met

momentarily, and I self- consciously scribbled some words in my

notebook that make only partial sense as I read them now:

''Giardello ducking me. Jersey isn't quitting.''

The reason for the intimate press conference quickly became

apparent as Tiger gave only the briefest answers to questions about

the match with Rivero. His special quality of voice and intelligence

hit me when, in a clipped colonial British accent braided with a

tribal African lilt, he said, ''The present champion refuses to meet

me again. He has defended only one time in 15 months and again it was

in his home city. I put it that this is not a courageous posture for

a so-called champion.'' Courageous posture? My god, who was this man?

''Why,'' a reporter asked, ''did you agree to fight Giardello in

Atlantic City, knowing that it was his backyard? Especially since you

were the champ?'' ''To a certain extent, it was because of his

problem in New York,'' said Tiger. The euphemistic ''problem'' was

well understood. Giardello hadn't had a license to box in New York

since 1957. It had been revoked because of what the athletic

commission called his ''undesirable connections.'' Word was out that

Giardello's management was mob controlled, or at least mob connected.

''But that is not the entire story,'' Tiger explained patiently.

''They offered me more money if I would fight him in Atlantic City. I

do not wish to seem the mercenary, gentlemen, but this is my

livelihood. I am not utterly disappointed -- with my purse I bought

a beauty shop for my sister and a bookstore in Lagos. Yes, these are

tribal scars.''

His last statement didn't make any sense. I didn't realize he was

speaking directly to me. I had been staring at his chest. His thick

finger moved over a band of thin, vertical scars, each about two

inches long, that formed a horizontal stripe almost from armpit to

armpit. ''Tribal scars,'' he repeated for my benefit. ''All Ibo boys

receive them when they have proved their courage.''

I was surprised by his easy assumption that we would know what an

Ibo was. I guessed correctly that it was the name of his tribe, his

people. Much of the world would come to know that name soon enough --

shamefully and tragically.

''A bookstore?'' I asked. ''Why would you want to buy a

bookstore?''

He flashed a smile that revealed a gold tooth. ''Because I like to

read books. Har, har. Why else?''

Dick Tiger had not called his press conference to discuss books

or book- stores. Instead, he continued to impress upon the other

reporters his arguments about why he should get a rematch with

Giardello and why it should be soon.

His best and most practical point was that the only decent payday

available for Giardello was to fight the true champion, Dick Tiger.

If Giardello did not offer him a rematch, Tiger said that he would

step up to fight light heavyweights. The winner of the Willie

Pastrano-Jose Torres fight for that title in a few weeks would be a

real possibility, said Tiger. He also vowed that once he stepped up

in class, he would never come back down. And, thus, Giardello could

kiss goodbye a profitable return match.

When Tiger had finished his statement, a reporter asked, ''You own

a fur coat?'' The fighter's brow furrowed, and he shook his head. The

reporter went on, ''You should have one, because Giardello will give

you another shot just about the day after hell freezes over.''

There were some perfunctory questions about Rivero; then someone

asked if there was anything Tiger would like to say directly to

Giardello.

''I respect any man who is a champion,'' Tiger said. ''Truly. I do

not blame him as much as the people who are behind him. But now he

must finally act like a champion and defend against the challenger

who has the strongest claim.''

''Isn't he just waiting until you're too old, until you lose your

edge?''

''He is as old as I!'' Tiger suddenly jumped into a ferocious

boxing % position; his face contorted into a sneer, and a snarl

rolled from a curled lip. He growled ominously, ''A Tiger never loses

his hunger.'' And, just as suddenly, he transformed himself back into

the affable, relaxed man who had charmed us. There was nothing left

to say. I waited until the other reporters had left.

Tiger asked me for whom I worked. ''I'm only a stringer for UPI.

Actually, I'm an English teacher,'' I said.

''Have you read Animal Farm?''

''Orwell?''

''Of course, Orwell.''

We spent the afternoon together, talking a bit about Orwell but

more about the implications of Animal Farm and the terrible pitfalls

of revolutionary politics. He seemed to have a personal interest. He

showered and dressed. His brown suit was on the shabby side, the

jacket a shade lighter than the pants; his black shoes had gray

scuffs. We walked briskly down Eighth Avenue. He was carrying a

heavily twined package that he wanted to go out in the afternoon

mail. It was destined for Aba, Nigeria.

I couldn't believe that, less than an hour after I had met him, I

was walking in Manhattan with the former middleweight champion of the

world. I assumed passersby recognized the celebrity and, by strong

association, me, too. In truth, almost no one noticed us. Those who

did happen to glance our way might have assumed that we were a

middle-aged black delivery man and a winded white intellectual.

The Ibo tribal scars on his chest, Tiger told me as we wove

through the crowds, were made by a very sharp, very hot knife when he

was 10, unusually young for the initiation. No, they didn't hurt

particularly. Then he corrected himself: An Ibo boy did not allow

them to hurt. When we were finally forced to stop for traffic, Tiger

looked at me carefully and said, ''The politics of my country are a

cause of great concern to me. There could soon be civil insurrection.

The situation is classically Orwellian.''

All the way to the post office and then back uptown he explained

the volatile situation in his homeland. ''Although we are not the

majority,'' he said, ''my people have held leadership in Nigeria

since the British left. In recent years, military elements have taken

control. We Ibo are not basically a militaristic people, but we will

not permit ourselves to be shunted aside. Without the Ibo, my country

would be a disaster.''

Then he said something that all these years later I recall with

clarity even though I hadn't written it down, perhaps because events

have since conspired to underline its bitter irony. ''Our opponents

call the Ibo the Jews of Africa. It is meant as an insult. I

interpret it as a high compliment.''

A few blocks farther north -- we were now on Tenth Avenue -- Tiger

stopped in front of a tailor's shop. He went inside, and I followed.

He pulled off his suit jacket and showed the man behind the counter a

long tear in the satin lining. The owner persuaded Tiger that it

would be better to select a secondhand jacket from the racks in the

rear than to have his own jacket repaired. Tiger and the tailor

disappeared. When they returned, Tiger was wearing another brown

jacket, a shade darker than the pants this time. The man wanted $5.

They settled on $2.50, his old jacket and a ticket to the Rivero

fight.

That bout proved remarkably easy for Tiger. Rivero was paunchy and

moved as though he were fighting underwater. Every punch he attempted

was of the KO variety. Tiger was hit cleanly just twice in 5 1/2

rounds. The referee stopped the fight in the sixth after Rivero had

been knocked down for the first time in 54 professional fights. Tiger

must have known that Rivero was just showing up for a payday.

He stayed busy after Rivero with a big win against rugged

''Hurricane'' Carter. If Giardello's people were waiting for age to

catch up with Tiger, it didn't seem to be happening. It is true,

however -- and all experienced fight people know it -- that a fighter

usually becomes old overnight. One fight, he has it all; the next,

nothing. Call it the Dorian Gray syndrome. Sometimes that change

takes place during a fight. Sometimes a fighter can lose it in a

single round. Maybe some sign of deterioration was what Giardello's

people were looking for. Maybe Tiger was foolish for not showing it

to them by fighting a little below his top level, but he was, after

all, an Ibo and proud.

On the boxing beat, word was that if it were up to Giardello

alone, he would have fought Tiger a year ago, that he wasn't really

such a bad guy. The problem was his management. They weren't going to

risk this championship with a tiger like Tiger. They knew Tiger was

already having trouble making the weight: he had come in five pounds

over the limit for Rivero. The thing that must have really thrown

them was that the Nigerian, for all his threats, still refused to

take on legitimate light heavyweights.

The scuttlebutt also had it that when they felt Giardello had one

good fight in him, and if Tiger was still available, they would shoot

for that last, nice payday and, who knows, maybe even go out a

winner. The consensus among experts was that Giardello, although not

a big hitter, could still do a good deal of cumulative damage to a

fighter as stationary as Tiger.

Then Giardello got rid of his manager and was given a license to

box in New York. A title match with Tiger in October 1965 was made

for Madison Square Garden. Giardello, as champion, dictated the

terms: $50,000 or 40% of the gate (live and home TV) while Tiger

would get $15,000 or 20%. I asked Tiger about the split, and he

said, ''He takes the lion's share, but I will take the Tiger's.''

His wit might have caused him to smile in self-appreciation, but it

didn't. He was frowning. There was trouble at home, he told me. He

had been sending every penny there to help the Ibo cause, but he was

worried about his family, his property, and particularly about his

ability to concentrate on this crucial boxing match, 5,000 miles from

the place and people that mattered most in his life.

''The world is never without its ironies,'' said the man with

tribal scars. ''Orwell understood that.''

During the week before the fight there was heavy betting. The

early money liked Giardello at 6 to 5. Then Tiger support came in,

and it was ''pick 'em.'' Then it was Tiger at 6 to 5; then, two days

before the bout, 8 to 5 Tiger. By fight time the odds were down to 7

to 5 Tiger.

More than 17,000 fans showed up at the Garden and paid more than

$160,000, so both fighters were sure of earning a lot more than their

guarantees. Frank Sinatra was supposed to be there. Mickey Mantle and

Yogi Berra had already been seen. I spotted Sugar Ray Robinson and

Rocky Graziano. There were more men in evening jackets and women

wearing furs than I had ever seen before at ringside.

And certainly more Africans than I had seen anywhere before. They

paraded through the crowd, some of them in tribal robes whose colors

had such a dark intensity about them that they made the garments seem

not only exotic but vaguely dangerous. Most of the men wore flat

hats with golden tassels.

Tiger came out first from the 50th Street side, and with his

appearance a large West African drum began to thunder rhythmically

from the darkness at one end of the arena. Its beat was alien but

compelling to the huge crowd of New Yorkers. They clapped and

stamped out a march beat, but the drum dominated the arena, as

foreboding as the drums in The Emperor Jones.

The fighters both weighed the precise limit of 160 pounds, but

Tiger was two inches shorter. Above his white trunks, Tiger's body

was massive. Giardello seemed pink and soft by comparison; his dark

trunks made his body seem even paler.

At the bell, Tiger rushed across the ring and met the champ before

he was two steps out of his corner. Tiger threw punches that backed

Giardello against the ropes. A surprise tactic. Tiger had always been

a very cautious starter, especially in a 15-round fight. Giardello

couldn't get off the ropes and was taking solid body shots.

Significantly, each time Giardello smothered Tiger's attack and

appeared to hook the dark arms, referee Johnny LoBianco quickly

stepped in and had them fighting again. That favored Tiger. His

fists worked Giardello's softening body. The great tribal drum

thundered. Before the first round was over, Joey Giardello had

become an old fighter.

To his credit, Giardello didn't let it become a rout. No, it

wasn't a great fight, but it went 15 rounds and it was very

interesting. The decision was unanimous. I scored it nine rounds to

six. Dick Tiger was champion again. Africans in green- and-purple

robes leaped into the ring carrying a banner that read BIAFRA MUST

LIVE. Few in the Garden understood its meaning.

After that fight Tiger had an increasingly difficult time making

the middleweight limit. Also, he had developed a pain in his lower

back and right side, a result of the Giardello fight. Eventually, the

presence of blood in his urine became commonplace. Nevertheless,

Tiger defended his middleweight title against Emile Griffith in 1966.

Weakened by pain and by the debilitating need to lose weight to meet

the limit, he lost a split decision. Then, eight months later, on

Dec. l6, he made good at last on his threat to move up into the light

heavyweight class. He won the championship easily by a decision over

Jose Torres.

He didn't stay long in the U.S. to enjoy it. There was great

trouble at home. The Ibo of eastern Nigeria had seceded from the

central government. They called their new country Biafra. The civil

war that followed became a rout. The Biafrans appealed for arms, for

aid. None was forthcoming: The Nigerian central government controlled

the army -- and the oil -- in black Africa's richest

petroleum-producing country.

Tiger returned to Biafra to fight another African in an exhibition

match at Port Harcourt, a few miles from his home in Aba. It was a

glorious day for the Ibo, and Tiger donated his purse to the

Biafran rebels. Later he would donate even more when, as a

38-year-old father of seven, he volunteered in the army of Biafra.

As a second lieutenant, he trained soldiers in physical exercises.

After his exhibition bout in Biafra, he returned to New York and

gave Torres a rematch at the Garden. Like their first fight, it drew

a pretty good crowd, and Tiger, giving away about 10 pounds, again

won by a decision. But this was the only touch of triumph in Dick

Tiger's life then. The ''Jews of Africa'' were being slaughtered. He

could get no word about the fate of his family. (As he later learned

that they were either dead or imprisoned.) He could not go home. His

properties in Lagos had been confiscated -- his apartments, his

service station in Aba, the beauty parlor and cosmetics shop, the

bookstore, the Mercedes, the tens of thousands of dollars saved by

the man in secondhand suits -- all were gone. Biafra, the dream, was

gone, too.

And soon -- too soon -- his title was also gone. In May 1968,

Tiger was knocked out two minutes into the fourth round by Bob

Foster. It was the only time Tiger had ever been knocked out. Perhaps

he should have quit then. The painful spasms in his lower back came

more frequently, but he couldn't quit. He was a political exile in

New York. He had no other salable skill.

Tiger fought four more bouts in New York, winning three and losing

one, a 10-round decision to Griffith. The fights gave him just enough

money to live on. After retiring in 1971 he worked as a porter at the

American Museum of Natural History, commuting by subway from a

furnished room in the Bedford- Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. In

October 1971 he was stricken at work by stabbing pains in his back,

right side and abdomen. It was an attack so severe that he fell to

his knees. He was taken to St. Vincent's Hospital in Greenwich

Village for observation.

No treatment was possible. He had cancer of the liver, acute and

advanced. He told me, ''The United States is a very good country, a

very nice country, but Biafra is my home. I will die in Biafra.''

Technically speaking, in 1971 no such place existed. But the

Nigerian government permitted Tiger to return to Aba, to his Ibo

home. For days after his return, thousands of visitors -- mourners,

really -- from miles around walked the hot, dusty roads to Aba. When

they found Dick Tiger's house, they saw a muscular but pain-withered

boxer sitting in front, in the shade of a solitary acacia tree. He

died on Dec. 14, 1971. END

Copyright 1986 Time Inc.

SAM TOPEROFF Sam Toperoff's ''Sugar Ray Leonard and,

PERSPECTIVE: DICK TIGER WAS A CHAMPION IN BOTH THE RING AND

HIS AFRICAN HOMELAND. , Sports Illustrated, 10-13-1986, pp 10.

BOXED INTO A CORNER

(Africa News Service)

Boxed Into A Corner

Lagos (Tempo, November 12, 1998) - Once the pride sport in Nigeria,

Boxing in the past two decades has declined steadily. Dieing with the

sport are its heroes most of whom now live in abject poverty and

neglect. Jacob Ajom met one of the relics of Nigeria's boxing glory

Kabiru Akindele in the throes of hunger and desperation

Hagard-looking, stern-faced with blood-shot eyes, he gallops in the

roped square, punching his tight fists in the air like one of the new

era spiritual soldiers of the pentecostal church. His fading track

suit, originally light blue with single deep-blue side stripes, now

wears a dark, muddy, brownish colour. His hair is bushy and his once

white training canvas are completely caked in dust. Suddenly, on

sighting this reporter, the man stopped his shadow-boxing and moved

towards his 'predator' to get a closer view. He wore an unkempt hair.

Casting a direct, determined look at the intruder and through his

sweat-dripping lips, he demanded, "Yes, oga, what can I do for you?"

Not getting an immediate response from the awe-striken reporter, he

sighed and turned away to a remote corner of the National Stadium

boxing gym, and sat on a desk. Sitting there, he looked tough and

determined, yet forlorn. Kabiru Akindele, a former national and West

African featherweight champion and number one contender for the African

and Commonwealth titles exuded anger, bitterness and frustration. His

lot has been that of rejection and abandonment by a country he has

spent the better part of his productive years for. Professionally, he

looks finished, but at 45, Kabiru believes strongly in his ability. The

former champ, who lost his title, due to inactivity in 1995, looks

forward to rediscovering his form to become a champion again.

The sad story of Kabiru Akindele is a reflection of the fate of

Nigerian boxers. Once the pride of Nigerian sports administrators and

numerous fans who thronged the sports hall to watch his fights, the

present situation of the boxer gives no idea of the past glorious days.

He's now hungry, jobless and on the verge of being ejected from his

place of abode.

His fortune is a sharp contrast to the opulence, comfort and millions

of dollars that his American counterparts can boast of. While the

American pugilist makes millions of dollar out of his talent and name,

coming in and out of retirement, this cannot be said of the Nigerian

boxer. Battered, underfed with little medicare during the heady days of

stardom, the boxer rarely has much left after a few years in the

limelight. The brain is grodgy and the body is meak. But he must

continue if he must survive. "I have lost my job," Akindele, wipping

his drenched forehead with the back of his palm, said. Continuing with

rehearsed deliberation, Kabiru, who, for decades fought in the colours

of the P & T Boxing Club (Now Nipost), said, since he lost his job, he

has been living in penury." I have not been paid my gratuity and nobody

says anything about it again."

Simply put, Kabiru has been reduced to the lowest dreg of the society.

While he awaits the payment of his gratuity from the Communications

Ministry, he has to make ends meet. Thus he works as an agbero (tout)

at the motor-park. He is paid a commission of between N5 and N20 for

his efforts, an amount that hardly can keep body and soul together.

Kabiru's ordeal is a reflection of the lot of former Nigerian boxers.

Most active Nigerian professional boxers can hardly meet their daily

basic needs-though with promising potentials, they are left in the

lurch as promoters shun them. Without fights, they definitely can't

make money. Paul Onwuachu, a national boxing coach, observed that "this

situation has put our boxers in a very desperate position, and made

them vulnerable."

The coach added that Nigerian boxers' conditions have made them to be

so cheapened that they could jump at any fee for fights both within and

outside the country. "Once a promoter dangles any figure before them,

they see it as an opportunity to eke out a living and perhaps catch the

eye of another promoter." Retrospectively, Nigerian boxing has come a

long way. Before the country's attainment of independence, Hogan 'Kid'

Bassey and Dick Tiger (both now of blessed memory), had caught the

attention of the world by becoming world champions. Unfortunately,

since those pre-independence landmarks, Nigeria has almost vanished

from the international boxing scene. No Nigerian has won any major

title in the paid ranks in recent times. Bash Ali's was the lone

crusader in Europe and even then his claim were quite questionable.

Obisia Nwankpa, Eddie Ndukwu, Dele Jonathan, Hogan Jimoh, Davidson

Andeh, Joe Lasisi and a host of others sparkled for a while winning the

West African, African and Commonwealth titles at different times. Some

of them raised the hopes of their compatriots for at least another

world title, but such dreams were never fulfilled.

"World titles will continue to elude us for as long as we abandon our

boxers to the machinations of foreign promoters," coach Onwuachu said.

"No Ghanaian or American would want to promote a fight that will

produce a Nigerian champion. No matter, except by knockout." Though the

boxers have complained of neglect, the consensus of boxing buffs is

that Nigerian boxers are generally lazy. "Most of them are not ready

for the hard work that will get them into the shape that past fighters

such as Eddie Ndukwu, Obisia Nwankpa, David Andeh and others attained.

Like the physician, the boxer must first heal himself.

Publication Date: 19 November, 1998

Copyright 1998 Africa News Service (via Comtex). All rights reserved

Author not available, BOXED INTO A CORNER. , Africa News Service, 11-12-1998.

I'LL ALLOW MY KID TO BOX

(Africa News Service)

I'll Allow My Kid To Box

Lagos (Tempo, March 25, 1999) - Once the toast of the boxing world,

Obisia Nwankpa spends his time away from fame, training young boxer's.

PETER DEMEYIN reports on the ex-boxer's exploits in the ring, his

regrets and projections He didn't look any different from the

generality who came to eat at the bukas that dot the mainbowl of the

National Stadium.

The fact that he was engrossed in his meal ("Apu" and Egusi soup) made

him more anonymous. The surroundings and his entire mien never gave an

inkling to his past.

Nobody gave him more than a casual glance and a solitary hello. It was

a far cry from the fame and popularity he enjoyed in the '80s. Then he

was the toast of not only the boxing world, but many fans and admirers,

especially ladies.

Then he was the real Obisia Nwankpa. Though his name was not changed,

he is no longer the Obisia Nwankpa of old. The old Obisia Nwankpa was

boxing champion who won many laurels and championships within and

outside Nigeria, high point being a shot at the world lightweight title

then held by Seoul Mamby.

That was in 1981. He enjoyed the blitz and glamour of boxing. Today,

Obisia evokes pity. He lives a life of near destitution. Neglected and

unsung, Obisia has resigned himself to fate.

"In Nigeria, people don't know how to celebrate their heroes. Rather,

they seize every opportunity to denigrate them. You should help tell

the public that Obisia Nwankpa is alive, hale and hearty." Obisia, who

speaks Yoruba very fluently, would not strike you as an average Igbo

man, despite hailing from Isialamogwa Local Government Area of Abia

State. Having been born in Lagos to Mr. and Mrs. Mathias Nwankpa in the

early '50s might be responsible for the ex-boxer's very "Western"

manners and accent. The former number one contender to the lightweight

crown of the world is one of the many Easterners whose education was

cut short due to the civil war of 1967-70.

"Even if I had gone to the university, I wouldn't have had the type of

fulfillment boxing provided me. When you talk of money and honour, I

had them in boxing. Again, boxing accorded me the opportunity to

travel to over 50 different countries in different continents. What

else do I want in life?"

Considering his antecedents, that Obisia fought for a world title is a

miracle in itself. He started boxing at Makpara Approach School, a

reform institution for children of Igbo men captured and adopted by the

federal government forces during the civil war. Between 1967-70, he was

the boxing champion in the school. For seven years, 1970-77, Obisia

fought in the amateur ranks in the colours of the Nigerian Army.

He joined the force as a corporal. Inspired by the late Dick Tiger and

Hogan Kid Bassey, Obisia won many laurels in the amateur ranks which

included gold medals at the 1973 All-African Games and the 1974

Commonwealth Games in New Zealand. When he turned professional in 1977,

it didn't take long for Obisia to establish himself as a force in the

paid ranks on the local scene.

In what he regarded as his toughest fight, Obisia remembers his clash

with Davidson Andeh. "My fight with Andeh, who was the reigning

lightwelter weight champion was a thriller, indeed. Most people didn't

expect me to win but I knocked him out in round eight. Andeh resigned

from boxing the following day."

Having won the African and Commonwealth titles by defeating Degis

Lorents and Jeff Malcomm respectively, the stage was set for Obisia to

have a crack at the world light weight crown held by Seoul Mamby of

America.

The fight was billed for Lagos. Before then Obisia had beaten many

boxers in their backyards . They included Englishman Chris Davis, Mike

Abbay of Guyana, Mika Hayana of Pueto Rico and Argentine Joan Gumene.

The world title fight against Seoul Mamby was to mark the turning point

in the career of Obisia.

Recalling the fight, Obisia's voice was laced with emotions tonged with

regret. "Before the fight, during training, I always weighed every

morning. nd myself and my British manager calculated that I weighed 65

kilograms. But before the fight, at the weighing in, I was one kilogram

overweight, which means I had to shed the extra weight by physical

training. Despite the weight problem, Obisia went to give a good

account of himself.

He recounts the tense moments after the fight: "After the fight, it

took the judges one and a half hours to announce the result. It was 2-1

against me. The two American judges gave it to Mamby, and the French

judge gave it to me. The bout was a charade." Asked what happened to

the banned substance caught with Mamby in the seventh round, Obisia got

visibly furious:

"I don't like talking about that fight because it was day light

robbery. From the video clips, I dominated the first seven rounds while

we shared two other rounds. How they came about the verdict I don't

know. I don't know why the NBB didn't follow up my protest." The defeat

marked a turning point in the life of Obisia. He was beaten twice by

Billy Famous, and to aggravate his woes, Obisia was dismissed from the

Nigerian Army for allegedly raping a minor. He refused to comment on

the rape charge. "I don't want to open old wounds," he declared.

Though Obisia collected $50,000 for the world title fight, and

generally made money during his career, his present state leaves much

to be desired. How did he spend his money?

"I think it would be foolish to ask me how I spent my money. Have you

seen anybody who made money and spent it on sand? I invested some of

the money on projects and some members of my family. Many people made

more money and are broke today. Didn't you hear about Muhammed Ali.

Even Pele was broke at a time. It's not peculiar to me."

Now a boxing coach, the father of three boys and four girls says he

would allow any of his kids, male or female, to take to boxing. His

priority now is to help young boxers excel in the forthcoming All

African Games and the Sydney 2000 Olympics.

Publication Date: April 1, 1999

Copyright 1999 Africa News Service (via Comtex). All rights reserved

Author not available, I'LL ALLOW MY KID TO BOX. , Africa News Service, 03-25-1999.

Akinwande gets huge chance to shake image as gentle giant

(USA Today)

NEW YORK -- If size really did matter, wow, can you imagine the swath

of menace Henry Akinwande would rip through the heart of the heavyweight

division, much less Evander Holyfield, Godzilla or a rush-hour Manhattan

taxi snarl?

Six-feet-seven. Nearly 250 pounds. He has the size to stalk, the jab

to punish. In theory, Akinwande should possess the paralyzing punching

power of George Foreman during his '70s heyday (the decade, not the

big fella's age).

Alas, Akinwande is boxing's gentle pterodactyl, more prone to flight

than fight.

The fighter's 86-inch wing spread is reputed to be the longest in

the sport since Italian giant Primo Carnera roamed the canvas more

than 60 years ago.

But his attention span for matters violent is one of the shortest.

Ultimately, that is what Holyfield, the littlest, bravest heavyweight

warrior, relies on Saturday night in their championship battle at

Madison Square Garden.

``It's obvious he can feel (intimidated), that's the way he looked

against (Lennox) Lewis,'' Holyfield says.

That's why Akinwande doesn't stand tall with fight fans. Only 10 months

ago, referee Mills Lane -- an ex-Marine unable to stomach the sight

of a grown man refusing to fight -- disqualifed Akinwande in the fifth

round for repeatedly clutching WBC champion Lewis.

``If he had beaten Lewis, I would've called him `Henry the First,'

'' says boxing scribe Colin Hart of The (London) Sun. ``As it turned

out, he was `Henry the Worst.' ''

Akinwande, son of a middle-class Nigerian businessman, became known

as Huggin' Henry. This despite displaying the kind of terrorizing

power forward frame that Chicago Bulls coach Phil Jackson would pay

untold millions to lay on Karl Malone of the Utah Jazz this week.

But where's the attitude?

``People say I have no guts, I have no heart,'' Akinwande says. ``They

do not know what I went through in my life.''

In less than two months, new trainer Emanuel Steward -- who supplanted

Don Turner, who also co-trains Holyfield with Tommy Brooks -- has

faced an enormous task in attempting to transform Akinwande's passivity.

As with many fighters, Steward says ``a lot of Henry's problems are

mental,'' brought on by his own insecurities.

``That's why I'm here,'' Akwinande says. ``To prove something.''

To himself. To the public. To his parents, who pleaded with him not

to get involved with boxing as a teen-ager. And to the great many

Nigerian athletes of his homeland, from the memory of middleweight

Dick Tiger to the present-day wonder of Hakeem Olajuwon.

Akinwande has come a long way from his job as a street sweeper in

south London, after he left home at 15 against his father Joseph's

wishes.

``In Africa, they look down on you if you get into sports,'' he says.

``The father tells you everything to do, even if you're 30. When he

found out I was boxing, he nearly killed me. He said I wasn't his

son anymore.''

They've since repaired the relationship. Saturday, Akinwande tries

to do the same with the public.

``My destiny,'' he says knowingly, ``is my hands.''

Copyright 1998, USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co., Inc.Jon Saraceno, Akinwande gets huge chance to shake image as gentle giant. , USA Today, 06-03-1998, pp 13C.

Philip Emeagwali

RECOMMENDED READING

He is an Intellectual Inspiration

Can Nigeria Vault into the Information Age?

CYBERSPACE GOSSIPS

You can read and/or join the following uncensored discussion threads:

Note: Pages will open in a new browser window.

GUESTBOOK ENTRIES

YOUR COMMENTS ON THE BIAFRAN WAR

Search : We have 1000 homepages on this web site.